Today, August 15, 2022, marks what would have been Julia Child's 110th birthday! To celebrate her accomplishments and support our "What's Cookin', Laurel?" food history exhibit, we are pleased to share with you this story from a local Laurel resident who was a friend of Julia's. Enjoy - and Bon Appetit! Julia and I had been friendship for many years. In fact, I was present and helping (as best I could) at every one of the cooking shows taped in her home in Cambridge. After those series were completed, we stayed in touch in many ways. I was present also for many of the shows she later did jointly with Jacques Pepin. Julia spent quite a lot of time in California, where she lived much of her childhood in Pasadena. She and Paul particularly liked Santa Barbara, long before it became so crowded. Our phone calls had become a longstanding tradition almost every Sunday morning, no matter where we were. She suggested that I join her for my 60th birthday. I thought that was a terrific idea! The plan was that we would drive to Napa from Santa Barbara, where she would also would meet with Robert Mondavi. Then we would go to one of her favorite places in the Wine Country where we would have a nice celebration. It was a long drive, but Julia loved to "get out and go!" She commissioned a car and driver, and on November 2, 2000, we set out in the morning. Of course, we had to stop at one of her beloved "In and Out Burgers" for lunch. We arrived in Napa and checked into our hotel. She went out for a business dinner with Mr. Mondavi, and I went out on my own.

She told me at breakfast that she and Robert Mondavi had agreed that a restaurant would be opened in Napa and it would be named "Julia's Kitchen." This would be the first (and only) time she had ever agreed to allow her name and reputation to be associated with a commercial venture. Although she would not be an owner, she would be in charge of dining standards and even menus opening months. She was so excited! November 3, we just wandered around. She was using a walker by that stage and had had back surgery, which made her a bit uncomfortable, but totally undaunted! We had a great day, and dinner someplace new that evening. The staff had never seen her before in person and it became a party of its own! Julia just loved it. So, the next day, November 4, 2000, was my 60th. Somehow she had planned something rather special. Her nephew Alex showed up, and we all went to a Mexican restaurant (I forget which one). Well....they had decked it out for a party! A few other folks I had known through Julia over the years also were there. We just had a blast, complete with a Mexican pinata! I had never seen Julia drink so much beer! Dos Equis. She said she loved beer with this cuisine and she was right! I have drunk Dos Equis ever since. Julia gifted me something which was very personal and very moving. November 5, we drove back to Santa Barbara. Julia had some business to attend to, but we got together for dinner that evening. More Mexican food! La Super Rica Taqueria.... Julia loved excellent Mexican cuisine almost as much as French. The next day I flew home. I did not know at the time that this would be the last time I would see her. We continued our phone calls but it was not the same as the in-person exuberance I had come to know and love. Julia would pass away four years later. Her calendar had remained full right up until the end. Photo credits: Julia Child in her kitchen as photographed ©Lynn Gilbert, 1978, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Lynn Gilbert, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons Julia Child's Kitchen on display at the National Museum of American History. RadioFan at English Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

1 Comment

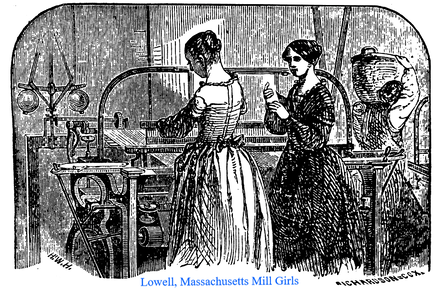

It’s Women’s’ History Month, and this might be a good time to look back at an often overlooked part of Laurel’s early workforce. In 1845, when the Laurel Cotton Mill was in full operation, the majority of its workers, were in fact women. According to “The Laurel Factory” an article in the August 1845 American Farmer. ...”[At] Col. Capron’s factory, where from 700 to 800 find constant and lucrative employment, a large portion of whom are female…” According to the article, only about 150 of the employees were men, who earned about $1.25per day, which would come to about $30/month for a 6 day workweek. Women, as they have on many other occasions, earned far less. Between $12 to $20/month. Or, between $.50-$.83/day. This was commensurate with the amount Mill girls were earning further North, in the industrial town of Lowell, Massachusetts.[1] [1] Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lowell_mill_girls accessed 3.7.22 Who were these women? Some came from nearby farms, crossing over to the factory from across what was then Anne Arundel, Howard District, but which in 1851 was renamed Howard County. Others likely came from nearby Prince George’s Farms. Some evidently boarded nearby, including in one of the stone homes on Main Street. The same American Farmer article notes that “The board of the men is $10 per month; that of the females, from $5 to $6. “ None of these women, or men, as far as can be ascertained, were people of color, which suggests that mill employment may have been closed off to Laurel’s African American community.

We know that both men and women in a family often worked in the mill. Tracking the number of women workers from the early years is difficult. The 1840 census doesn’t list occupations, and in 1850 it was only interested in the occupations of male persons (not female) over age 16. The 1860 census, which shows occupations for all in the household lists very few mill workers at all, and only eight women, which begs the question of whether the mill was in operation when the census was taken. The 1870 census, which lists all occupations, gives us a slightly clearer picture of these working women when the mill was in full operation. In Laurel Factory (which didn’t include nearby communities or Howard County), the census lists at least 158 women as working at the cotton mill. Some, like the Waterman family profiled in the Laurel Museum’s 2012 exhibit “True Life: I‘m a Laurel Mill Worker”, had a daughter as young as six and other girls ranging from 12 to 17 working in the cotton mill. (All the household’s sons, aged 9, 17 also worked there) Several families in the 1870 census list women with different last names than the head of household. Were these boarders or relations? It’s difficult to know. Although young children would also work, they also may have had the opportunity to go to school. Horace Capron had provided for some education, as noted in American Farmer. “Col. Capron has erected a school-house…with a competent teacher – here the children receive their education gratuitously...” We don’t know how many of these children actually attend school or to what grade? A school building is noted in the 1861 map of Laurel. We don’t know, though by the 1870s Laurel did have a public school. In 1878 Mill Superintendent George Nye noted the opening of the public school with 130 students. There is much we don’t know about the life of Laurel’s female mill workers. The life of early cotton mill girls has been well documented at the Lowell Massachusetts cotton mill site https://www.nps.gov/lowe/learn/historyculture/the-mill-girls-of-lowell.htm. How much of their experience translates to that of Laurel women is unknown. Hopefully future research will uncover more of their story. For additional resources on mill girls visit: http://resourcesforhistoryteachers.pbworks.com/w/page/125185421/Lowell%20Mill%20Girls by: Karen Lubieniecki  Lisa and Dave Everett are the owners of the Laurel Manor House Bed & Breakfast, located at 1110 Montgomery Street, the site of Prince George’s County first B&B. The couple purchased the historic property in 2011, and moved into the house the following year. Even though they had lived just four miles from Laurel in Howard County, they were not aware of Laurel’s history until the house beckoned. The historic inn was built in 1888 by businessman Edward Phelps, who would become mayor of Laurel in 1897 and serve for seven terms. The Phelps family moved out of the house in 1915. It was in tracking down the history of the property and Phelps family that Lisa first connected with the Laurel Historical Society and her Oldtown neighbors. Lisa knew that she wanted to run a B&B and the Phelps mansion held many possibilities. Although the property was livable, it required much work to convert the house not only to modern standards, but also to accommodate guests. Fortunately, Dave is an engineer by trade and handyman and landscaper around the property. The pair make a great team, complementing each other’s talents and abilities. The team spent almost seven years renovating the historic structure, completing major projects like adding bathrooms and upgrading utilities. However, they were careful to retain many original features and preserve the details of the house that they had fallen in love with, such as the door hinges and window latches. Their preservation ethic was recognized in 2019, when they were awarded the “Best of Maryland Community Choice Award” by Preservation Maryland. Their labor of love had been nominated by the City of Laurel, who had long been champions of the Everetts and their rehabilitation project.

Lisa enjoys being an innkeeper and the opportunity to connect to different visitors, engaging newcomers in the history and city of Laurel while serving delicious made-from-scratch baked goods and breakfasts. Since the B&B is a walkable distance to Oldtown Laurel, guests enjoy taking a stroll to get dinner or enjoy the other historic buildings in the area. Lisa recognizes the changes along Main Street in the years that they have lived here, pointing out the positive growth and improvements, and the arrival of diverse new businesses and restaurants. After a period of closure due to the pandemic, the Laurel Manor House B&B is set to open again, as the Everetts continue to lovingly work on their house and welcome new visitors to Laurel. LHS interview, 2021. Photo credit: Lisa Everett CLICK HERE for the PDF version.  Deborah Randall is the founder of Venus Theatre, the longest running regional women’s theatre in the nation. Located at 21 C Street in Laurel, the company has produced at least 70 woman-empowering scripts and given over 1000 opportunities to an array of artists. Venus Theatre was established in 2000 and it arrived at its Laurel location in 2006. Previously, Deborah toured shows and ran improv performances under the title Venus Envy. This name was born out of the SHE Company in Washington, DC, which led Take Back the Night marches and empowerment workshops at House of Ruth. When Venus Theatre first opened, Deborah offered classes, summer camps, and workshops to parents and children. She and her husband, Alan Scott, wrote three different musicals for children: Juanita the Walrus Goes on a Shopping Spree, Boogsnot and the Disco Dancing Snows and Fiona the Fish and the Musical Carwash. She eventually returned to her true passion of presenting solo shows and women’s empowerment plays. In addition to performing work written by other artists, she resurrected her own solo show titled Molly Daughter, which is now published through Chicago University Press. Deborah even makes sustainable creativity a priority. Venus Theatre recycles set pieces and borrows to avoid building. Deborah is also a trained actor who once performed political satire in Washington, DC. However, she considers herself as more of a writer. This prompted her to develop and perform solo shows. She later made a shift to more collaborative productions and started reading the work of other playwrights. Deborah hosts public staged readings, which involve holding the script and reading from the play, often with the use of music stands. She describes staged readings as “a part of the theatrical creative process which allows writers to get out of their head with the work, take some feedback and make any necessary adjustments.”

Deborah Randall has amplified the voices of women and children for over twenty years. Her work not only contributes to the history of arts and activism in Laurel, but it also makes an impact on women’s history throughout the nation. CLICK HERE for the downloadable PDF version. Materials from LHS collections and interview, 2021, M. Sturdivant Photo by: Marvin Joseph, The Washington Post  The Honorable Valerie Nicholas has been a Laurel history maker since her appointment to the Laurel City Council in 2011. She is the first and only African American woman to serve in the role, to date. A highly spiritual woman, Valerie said, she saw an ad in the Laurel Leader for the Council seat vacancy, upon the resignation of former Councilwoman Gayle Snyder and God said, Valerie make your petition. Even though she had doubt, she did and she was appointed. From that date to this, she has remained undefeated for re-election. Valerie continues to make history as the first African American to hold the Council At-Large position since 2019 and her 2020 nomination as the first African American woman to serve as City of Laurel Council President. Valerie is a compassionate community servant and considers her role as a “labor of love and legislation”. 2011 was an inspirational year for her, as in addition to adjusting to her new role as Councilwoman, she also revived her non-profit, Love Is Not Enough, Inc.. This organization was born from her own painful experiences of Domestic Abuse, from a young girl to adulthood. The work she does in the name of her organization is her way of turning her pain into purpose and honoring the grace she feels from God, to live to tell her story. Though Valerie works full-time as a Patient Advocate at the new Adventist HealthCare White Oak Medical Center; she is up every morning at 3:00 am with a full trunk of groceries, toilet paper, toiletries, masks, hand sanitizer and more, to make deliveries to people in need; before going to work. She has established strong donation partnerships over the years and now has two full storage units of supplies. In April of 2020 Valerie’s organization received its first Maryland state grant. She is now able to deliver service throughout the state.

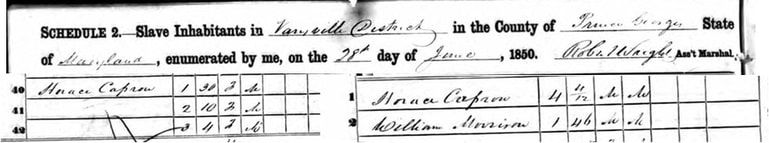

Prior to Valerie’s life pivot to City Council and business owner, she worked for the Federal Government for 20 years, until her resignation, to selflessly become a full-time caregiver to her brother undergoing dialysis treatments, over 17 years; until his passing. Before her current role at Adventist HealthCare Medical Center, she worked 8 years at the former Laurel Regional Hospital, as a Chaplain, Volunteer Recruiter, and Patient Advocate. Valerie says that most people don’t turn to her for help with getting a street paved or adding a stop sign. Most of the time, people turn to her for help with housing assistance, employment, job readiness, food, help with utility bills, transportation, and other basic needs. She makes it her mission to leave people better than she found them. She has been called the “Wounded Healer”. Valerie considers it an honor to reside in and serve the City of Laurel. She points to the Main Street Business Grants and the City-wide public Wi-Fi, that is so critical to those without access, among her most proud legislative accomplishments. Valerie is ready to continue making history in and out of Laurel. CLICK HERE for the PDF version of this article. Sunday March 20, 2021 LHS Interview ~AVF  While much of the nation’s attention has focused on removing many monuments and renaming streets that honor slaveowners and Confederate heroes, little attention has been given to the issue, or even identifying those who owned enslaved people here in Laurel. An examination of the 1840, 1850 and 1860 slave census reveals that many early Laurel founders and honored citizens were in fact, slaveowners. Robert Pilson, a Laurel Factory superintendent owned five enslaved persons; William Warfield, owner of a store on upper Main Street, owned two. Jesse Duvall, whose shop and possibly Post Office were on lower Main Street, one. Not surprisingly perhaps, Theodore Jenkins, owner of Montpelier, and a key figure in both the Laurel Cotton Mill and the founding of St. Mary of the Mills Catholic Church had 14 enslaved persons at the last (1860) slave census. More surprising to some might be the fact that his brother-in-law Horace Capron owned enslaved people for at least 10 years.  Capron, recognized as a founder of Laurel and builder of many mill worker houses owned four enslaved people: one woman and three children. Their names do not appear in either the 1840 or 1850 slave census, but in Capron’s 1851 bankruptcy documents, the woman, aged 30, is identified as “Betsey,” and lists three children. It is possible that they entered his household from his wife, Louisa Snowden, whose sister, Juliana, was married to Theodore Jenkins, but we can’t be sure. We tend to focus on Capron’s accomplishments as an early Mill owner, and his role as builder of some of Laurel’s iconic mill houses, including today’s Laurel Museum. But Capron’s main personal interest was in farming, and he owned large tracts of land in Howard County, and in Laurel. In fact, his “Laurel Farm” as it was called, was more than 1000 acres, and aside from Main Street, encompassed much of what is today the City of Laurel east of 7th Street to Washington Blvd, and South to Laurel Lakes. The farm had 12 tenements, and it may be the farmers on these properties tilled the Capron land. The other possibility is that Capron hired freedmen, or hired enslaved labor. Or perhaps his manager supplied the laborers.  Laurel Farm was put up for auction in 1852, and approximately 800 acres were ultimately purchased by Thomas J. Talbott, who, according to A Church and its Village by Sally Bucklee, p.143, was “resident proprietor and past manager of the Laurel Farm. “ In 1850 Thomas J. Talbott had owned an exhausted tobacco farm in Elkridge, which he sold. By 1853 he was living in Laurel and operating the former Capron farm, well known for its improved lands, and crops of oats, timothy and wheat. Its dairy had, at least in the past, sold milk in the District of Columbia. Thomas J. Talbott, (1804-1869) in the 1860 census recorded Laurel’s largest number of unnamed, enslaved people – nineteen. In 1860 Talbott lived in the house that still stands on Prince George Street. His 800 acres of land extended from Main Street to somewhere near what is now Laurel Lakes. Who worked this farm? Past tenant farmers? Possibly. In 1860 Talbott owned nine enslaved men and three women aged over ten. The census listed eight children (six females, two males) under 10. it is likely that at least some if not all of these enslaved people were involved in farming his extensive property and were critical to its prosperity.  Even before Talbott’s death in 1869, he had started to sell off plots. The McCeney home at 400 Main was built in 1866. Within eight years of his passing, the family had sold off much and subdivided most of the property, as shown in the 1878 Hopkins map of Laurel. At this point, we don’t know what became of the enslaved persons on the Talbott land, who would have become free when Maryland abolished slavery in 1864. We can speculate that the loss of slave labor affected the ability to successfully farm the property.  Talbott was evidently a pillar of St. Phillips Episcopal Church, and he and his wife are buried in its churchyard. It is highly probable that Talbott was a strong Confederate sympathizer. Two of Talbott’s daughter’s married brothers who were slaveholders in Essex County, Virginia. Another daughter married Theodore Jenkins’s son Francis. Since Talbott’s land went down to Washington Blvd, it must have been with some chagrin (or worse) that he viewed from the front of his house the Union troops stationed at the railroad throughout the war. Talbott’s place as Laurel’s largest owner of enslaved people raises the issue of who we honor in our community. Talbott Avenue, one of Laurel’s prominent roads, is named after its largest slaveholder. Perhaps it is time to reconsider Talbott Avenue and rename it after someone, or some part of Laurel that doesn’t honor its largest slave holder. But, some might object, the newly incorporated city was also honoring an early Commissioner and fourth President of the Board of Commissioners, John A. Talbott (1845-1910), son of Thomas J. But John Talbott was only 24 when named a commissioner, just months after his father’s death. The fact is that NONE of the other early commissioners, commission presidents or founders are so honored. And while today Talbott Avenue extends from Rt. 1 to 9th Street, in the 1878 Hopkins map, the original Talbot(sic) Avenue only ran one block: between Washington & Baltimore Turnpike (Rt 1 S. today), and what was then 2nd Avenue. Sally Bucklee clearly believed the senior Talbott was the one honored. On p. 227 of her book she notes “…three major streets all in a row [Talbott, Gorman and Compton] are named after distinguished 19th C members of St. Phillip’s and the community.” Sally Bucklee never mentions John, and he is not listed in the 1880 Laurel census. At some point he moved to the District of Columbia, where he died in 1910. As we tell the story of Laurel’s history, it is important we expand our understanding of who its early residents were, and all the elements of their stories. Recognizing the full history of the community and its founders and their accomplishments, and shortcomings is important. Honoring our largest owner of enslaved persons when we do not honor other early founders, or the enslaved persons or communities that made Laurel the town it is today is a statement in itself. And one perhaps we should change. Karen Lubieniecki 3.18.21  Gertrude Poe was a pioneer for women in law and journalism. Known as “Maryland’s First Lady of Journalism,” she was editor of The News Leader, now The Laurel Leader, for 41 years. Gertrude graduated from Laurel High School in 1931, at the young age of 15, and took a job as legal secretary for George McCeney. Poe graduated in 1939 from the Washington College School of Law and returned to work for the law offices of Bowie McCeney at 357 Main Street in Laurel. However, McCeney handed her control of the local newspaper, which he had recently acquired. At the helm of the Leader, Gertrude reversed the decline in readership and the publication thrived. She wrote a weekly column called “Pen Points,” which was like a personal note to her readers addressing local and national issues. Gertrude covered the news of a changing world with passion and professionalism. During World War II, Poe also managed The Bowie Register, The College Park News, and The Beltsville Banner, and became a broadcaster at the WLMD radio station in Laurel. In 1958, she became the first woman president of the Maryland Press Association. She received the Patriotic Civilian Service Award in 1963, for bringing attention to the base issues at Fort Meade. Her exacting standards resulted in many local and national journalism awards, including for her coverage of the George Wallace shooting in 1972. Poe retired from the Laurel Leader in 1980. In 1987, Gertrude was the first living person and first woman inducted into the Maryland-Delaware-DC Press Association Hall of Fame. She was also inducted into the Maryland Women’s Hall of Fame in 2011.

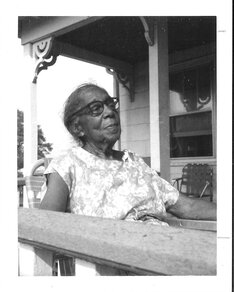

Gertrude Poe was a published author, patron of local arts and culture, and dedicated supporter of the Laurel Historical Society. In 2004, the Laurel Historical Society honored her at our annual Gala, themed as The Wizard of Oz. Known for her chic sense of style, the beaded emerald-green gown she wore to this event was one of her two dresses displayed at the Maryland Historical Society’s exhibit Spectrum of Fashion in 2019. LHS has several of her personal and iconic items in our collection, including her electric typewriter and small oak desk. Gertrude Poe passed away at her home in Ashton in 2017, at the age of 101. In a 2016 Laurel Leader article, a year before her passing, Gertrude wrote that hers had been “a good life and a good livelihood.” Click HERE for the downloadable PDF version. Information and photograph pulled from LHS collection and exhibit files. ~Updated 2021  Randy Kroop is a fourth-generation shoe and boot maker. Her family name is synonymous with high quality leather boots. As a teenager, Randy’s grandfather, Adolph Michael Kroop, known as “Mitch,” emigrated from Latvia, Northern Europe and made his way to Baltimore, Maryland; where he opened his first shop, near Pimlico Park, in 1907. He later moved to set up shop on Main Street in Ellicott City, across from Kaplan's Department Store and in 1927 he took occupancy in a building on Laurel’s Main Street. By the 1960’s he expanded and relocated operations to the leather factory building, A.M. Kroop and Sons, on C Street. Being located near Laurel Park, Kroop specialized in riding boots for jockeys, who required very sturdy yet lightweight boots in sizes much smaller than the typical man’s shoe. Kroop boots, using the tagline “often imitated, never duplicated,” were worn by famous jockeys and celebrities. Mitch Kroop made boots for Red Pollard, the jockey who rode Seabiscuit to fame in the late 1930s. In 2003, when the movie Seabiscuit was made, Randy made the reproduction boots for the actors. She also made riding boots and jockey boots for the movie Secretariat, released in 2010. Carly Simon, Madonna, and Leon Redbone are also included in their customer roster. From the beginning, A.M. Kroop and Sons was a family business. Having learned to cobble from his father, A.M. Kroop taught his sons the trade, while his daughter helped with bookkeeping. Randy recalls childhood days spent at the factory, and when the jockeys came into the shop in the mornings since they rode in the afternoons. Randy was very skilled in sewing and made many of her own clothes growing up, often because they did not have the means to buy the pretty clothes the girls in her school wore. But this talent, work ethic, and hands-on attitude were a perfect fit when it came time for the next generation to take over the family business. At the time, the horse racing industry was changing, and Randy soon specialized in helping people with problem feet or those wearing braces to have custom shoes that actually fit. She remembers these experiences as very rewarding. She inherited ten employees who had worked with her grandfather and/or her father. Many of them had watched her grow up from a little girl, which added to the challenge of being their new manager. Her given name worked to her advantage in many cases, as people assumed the owner was a male, or that she was one of the “sons” in the business. However, the work was very difficult and labor intensive, involving many steps in the boot-making process. The machines were big and heavy, and required a lot of training. Randy took on new employees over the years. However, she operated alone by the time of her retirement in 2019. She still keeps in touch with some of the grandchildren of those employees, fondling recalling the time a former employee - the first female hired by her grandfather- chose for her 80th birthday present to return to Laurel (from Delaware!) and visit the factory one more time. Randy remembers her walking right over to her old sewing machine. The woman was French-Canadian, and Randy remembers that her father and grandfather often hired refugees or immigrants, including other Jewish families. Although the Kroops lived in Baltimore, they were one of about only five Jewish families working in Laurel, at the time. Randy recalls other changes to the industry. When she started, Randy remembered when jockey boots were wearing size 2 or 3 boots; the famous jockey Willie Shoemaker had a size 1 last. But toward the end of her career, it was common to make bigger boots for jockeys who were 5’7” or so in height. Randy also specialized in riding boots for motorcycle police, indicating that one pair she made had a boot shaft of 21 inches around! Although she did not grow up in Laurel, Randy spent many days of her childhood in the family factory. She remembers when Laurel had a reputation for being “shady” and remembers that her father kept the children away from the racetrack. It wasn’t until she took her dogs out for walks along Riverfront Trail that she started to get to know the history of Laurel. She remembers long walks and conversations with Jim McCeney and Jim Frazier, who pointed out historic buildings and places of interest. Today, Randy Kroop is keeping busy in retirement and misses her old family shop. She has donated many items to the Laurel Historical Society, adding to our history and knowledge of a family business that has celebrated being in business ‘for upward of a century.” Information and photograph pulled from LHS collection files and oral interview with Randy Kroop, 2021. Click here for the PDF version of this article.  Catherine Johnstone Hopkins, lovingly called “Miss Katie”, was born in the Grove neighborhood of Laurel, in 1906. Her parents were Elizabeth and Frank J. Hopkins. The surname is suspected to have been given from ancestral enslavement.* Miss Katie was one of only two children. Her sister Ethel died just seventeen days before her 100th birthday and Miss Katie lived in Laurel for all of her 105 years. She attended day and night school in Prince George’s County and was taught piano lessons from Mrs. Dora Mack Carter, of the entrepreneurial Carter family of Guilford, MD; the first black woman to provide private music lessons in Howard County and own a country music studio. Miss Katie grew to share her talent as a singer, during the 1940s, in the Union Gospel Chorus, a local community band and as the organist and pianist, 46 years in service to St. Mark’s Church, for which she received recognition. During her early years of employment, she worked with children at the St. Mildred’s Academy; known today as St. Mary of the Mills School. She later worked as a seamstress at Ft. Meade, during WW II, a job for which she expressed a lot of love and enjoyment.

Thereafter, she was employed at the University of Maryland for many years. Through her retirement in 1973, Miss Katie worked at the O.W. Phair Elementary School, which was located at 1100 West Street (intersecting with Park Avenue). The school ceased operation around 1979 and was later renovated and used for temporary WSSC offices in the 1980s. Prior to the passing of Miss Katie and her sister Ethel, both sisters were featured in a 1983 Laurel Leader article**, where they described remembering when there was an oak grove in the Grove community, named for the stately, shady trees. They also recalled when the streets were dirt roads and the sidewalks were wooden boardwalks. Photograph and information pulled from the Laurel Museum Collection. Updated~Laurel Historical Society/AVF2021 *In 2020, new evidence showed that Johns Hopkins claimed four men as his property on the 1850 Census and often had business dealings using Black people as collateral). https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/12/09/johns-hopkins-university-founder-enslaved-people/ **The Grove: Rooted in a Proud Tradition.” Laurel Leader, September 1, 1983 CLICK HERE FOR THE PDF VERSION OF THIS POST.  Bertha Levi Moore arrived in Laurel at 11 months old. She attended the first “Colored School #2”, located at 803 West Street, with 54 other children and a single teacher. When she became of high school age, Laurel High School was open to white students only. Bertha boarded with a family in Washington, DC to attend high school classes offered by Howard University. Bertha would herself become a school teacher and teach at the “Colored School #2” where she was first educated. She settled in Laurel, eventually marrying. She and her husband built a house on 10th Street and were considered “Blockbusters”, as the first African Americans to reside on that block. They farmed their plot of land and sold their produce, while raising 13 children. Bertha’s accomplishments were significant, as she was the daughter of slaves. Her father escaped slavery and eventually joined the Union Army to fight in the Civil War. Her mother would have been considered fortunate, at the time, learning to read and write from white teachers traveling from the northern states to give free lessons to black children. Her mother’s last name was Hall, suspected to be named after the Hall family, to whom she was enslaved. They lived in a small African American town off Rte.197 in Laurel called Halltown. In the 1890s, Bertha’s parents were among the earliest members of St. Mark’s church, still thriving at 601 8th Street.

During an interview in the 1970s, Bertha shared memories of the Laurel Sanitarium for mental illness and the Keely Institute for the treatment of alcoholism as being the primary employment for African Americans at the time. Prior to its relocation to the grounds of the Laurel Sanitarium, the Keely Institute was located at 5th and Talbott Streets, which was the dividing line between the black and white communities. She recalled memories of the local chapter Ku Klux Klan burning crosses at Ivy Hill Cemetery and near St. Mary of the Mills Church on 8th Street. Photograph and information pulled from the Laurel Museum Collection. Updated~Laurel Historical Society/AVF2021 CLICK HERE FOR THE PDF VERSION OF THIS POST |

AuthorContributions by Laurel Historical Society staff and volunteers. Submissions welcome! Archives

August 2022

Categories |

LAUREL HISTORICAL SOCIETY

History & Happenings Blog

Home

|

Site Map |

Laurel Historical Society

817 Main Street Laurel, MD 20707 301-725-7975 [email protected] Laurel Museum Hours: Friday - Sunday 12-4 pm Research and Tour groups by appointment. |

© COPYRIGHT 2015-2023. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed