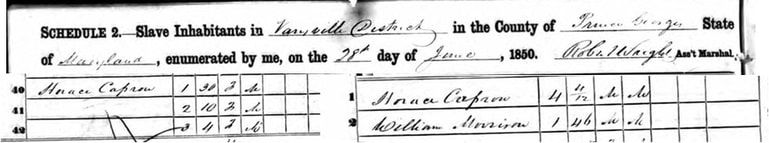

While much of the nation’s attention has focused on removing many monuments and renaming streets that honor slaveowners and Confederate heroes, little attention has been given to the issue, or even identifying those who owned enslaved people here in Laurel. An examination of the 1840, 1850 and 1860 slave census reveals that many early Laurel founders and honored citizens were in fact, slaveowners. Robert Pilson, a Laurel Factory superintendent owned five enslaved persons; William Warfield, owner of a store on upper Main Street, owned two. Jesse Duvall, whose shop and possibly Post Office were on lower Main Street, one. Not surprisingly perhaps, Theodore Jenkins, owner of Montpelier, and a key figure in both the Laurel Cotton Mill and the founding of St. Mary of the Mills Catholic Church had 14 enslaved persons at the last (1860) slave census. More surprising to some might be the fact that his brother-in-law Horace Capron owned enslaved people for at least 10 years.  Capron, recognized as a founder of Laurel and builder of many mill worker houses owned four enslaved people: one woman and three children. Their names do not appear in either the 1840 or 1850 slave census, but in Capron’s 1851 bankruptcy documents, the woman, aged 30, is identified as “Betsey,” and lists three children. It is possible that they entered his household from his wife, Louisa Snowden, whose sister, Juliana, was married to Theodore Jenkins, but we can’t be sure. We tend to focus on Capron’s accomplishments as an early Mill owner, and his role as builder of some of Laurel’s iconic mill houses, including today’s Laurel Museum. But Capron’s main personal interest was in farming, and he owned large tracts of land in Howard County, and in Laurel. In fact, his “Laurel Farm” as it was called, was more than 1000 acres, and aside from Main Street, encompassed much of what is today the City of Laurel east of 7th Street to Washington Blvd, and South to Laurel Lakes. The farm had 12 tenements, and it may be the farmers on these properties tilled the Capron land. The other possibility is that Capron hired freedmen, or hired enslaved labor. Or perhaps his manager supplied the laborers.  Laurel Farm was put up for auction in 1852, and approximately 800 acres were ultimately purchased by Thomas J. Talbott, who, according to A Church and its Village by Sally Bucklee, p.143, was “resident proprietor and past manager of the Laurel Farm. “ In 1850 Thomas J. Talbott had owned an exhausted tobacco farm in Elkridge, which he sold. By 1853 he was living in Laurel and operating the former Capron farm, well known for its improved lands, and crops of oats, timothy and wheat. Its dairy had, at least in the past, sold milk in the District of Columbia. Thomas J. Talbott, (1804-1869) in the 1860 census recorded Laurel’s largest number of unnamed, enslaved people – nineteen. In 1860 Talbott lived in the house that still stands on Prince George Street. His 800 acres of land extended from Main Street to somewhere near what is now Laurel Lakes. Who worked this farm? Past tenant farmers? Possibly. In 1860 Talbott owned nine enslaved men and three women aged over ten. The census listed eight children (six females, two males) under 10. it is likely that at least some if not all of these enslaved people were involved in farming his extensive property and were critical to its prosperity.  Even before Talbott’s death in 1869, he had started to sell off plots. The McCeney home at 400 Main was built in 1866. Within eight years of his passing, the family had sold off much and subdivided most of the property, as shown in the 1878 Hopkins map of Laurel. At this point, we don’t know what became of the enslaved persons on the Talbott land, who would have become free when Maryland abolished slavery in 1864. We can speculate that the loss of slave labor affected the ability to successfully farm the property.  Talbott was evidently a pillar of St. Phillips Episcopal Church, and he and his wife are buried in its churchyard. It is highly probable that Talbott was a strong Confederate sympathizer. Two of Talbott’s daughter’s married brothers who were slaveholders in Essex County, Virginia. Another daughter married Theodore Jenkins’s son Francis. Since Talbott’s land went down to Washington Blvd, it must have been with some chagrin (or worse) that he viewed from the front of his house the Union troops stationed at the railroad throughout the war. Talbott’s place as Laurel’s largest owner of enslaved people raises the issue of who we honor in our community. Talbott Avenue, one of Laurel’s prominent roads, is named after its largest slaveholder. Perhaps it is time to reconsider Talbott Avenue and rename it after someone, or some part of Laurel that doesn’t honor its largest slave holder. But, some might object, the newly incorporated city was also honoring an early Commissioner and fourth President of the Board of Commissioners, John A. Talbott (1845-1910), son of Thomas J. But John Talbott was only 24 when named a commissioner, just months after his father’s death. The fact is that NONE of the other early commissioners, commission presidents or founders are so honored. And while today Talbott Avenue extends from Rt. 1 to 9th Street, in the 1878 Hopkins map, the original Talbot(sic) Avenue only ran one block: between Washington & Baltimore Turnpike (Rt 1 S. today), and what was then 2nd Avenue. Sally Bucklee clearly believed the senior Talbott was the one honored. On p. 227 of her book she notes “…three major streets all in a row [Talbott, Gorman and Compton] are named after distinguished 19th C members of St. Phillip’s and the community.” Sally Bucklee never mentions John, and he is not listed in the 1880 Laurel census. At some point he moved to the District of Columbia, where he died in 1910. As we tell the story of Laurel’s history, it is important we expand our understanding of who its early residents were, and all the elements of their stories. Recognizing the full history of the community and its founders and their accomplishments, and shortcomings is important. Honoring our largest owner of enslaved persons when we do not honor other early founders, or the enslaved persons or communities that made Laurel the town it is today is a statement in itself. And one perhaps we should change. Karen Lubieniecki 3.18.21

2 Comments

Abby Chapple

3/20/2021 05:54:00 am

Interesting and a challenge for small communities. I wonder about Berkeley Springs.

Reply

Teresa

3/21/2024 04:31:51 pm

I appreciate this article so much ! In a world where hiding & changing history seems to be the trend of America today, it’s refreshing to read an article where truth & accountability trumps that! What saddens me is this is only one example of so many enslaved people men, women, & children who go nameless, & they’re moved/ unmarked gravesites that could cover every inch of soil in he United States.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorContributions by Laurel Historical Society staff and volunteers. Submissions welcome! Archives

August 2022

Categories |

LAUREL HISTORICAL SOCIETY

History & Happenings Blog

Home

|

Site Map |

Laurel Historical Society

817 Main Street Laurel, MD 20707 301-725-7975 [email protected] Laurel Museum Hours: Friday - Sunday 12-4 pm Research and Tour groups by appointment. |

© COPYRIGHT 2015-2023. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed